At the end of a book in which he fires off a warning flare about the trajectory of modern science, C.S. Lewis pauses to envision what “regenerate science” might look like.

“Is it, then, possible to imagine a new Natural Philosophy, continually conscious that the ‘natural object’ produced by analysis and abstraction is not reality but only a view, and always correcting the abstraction? … The regenerate science which I have in mind would not do even to minerals and vegetables what modern science threatens to do to man himself. When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole. … Its followers would not be free with the words only and merely. In a word, it would conquer Nature without being at the same time conquered by her and buy knowledge at a lower cost than that of life” (The Abolition of Man).

I don’t know if anyone before me has ever been struck by the phrase “regenerate science,” but what those two words do together is gather up a field of human endeavor that is now deeply atheistic, materialistic, and rationalistic and shine theological light on it. For those who agree that the gospel is meant to transfigure absolutely every square inch of human life, this opens up a fascinating possibility: that science may one day give us cures without side effects, progress without pollution, technology with telos.

I am a pastor, not a scientist. I am on the far opposite end of the professional spectrum from scientists. This is one man on the outside looking into a grand human effort that has given us vastly better living conditions, but also unleashes horrors every so often. And here is what has me thinking: what would it look like for the Kingdom to arrive in our labs and our research facilities? What kinds of products might we make if we knew how to read the significance of the created world—or even if we just believed the world was created to begin with?

Matthieu Pageau writes that the modern way of understanding anything is to ask, “What is it made of and how does it work?” While for the ancients, the question was, “What does it mean? What is its significance?” The former questions yield material knowledge and power over the natural world; the latter put us in touch with the Creator. Answering the former can tell us a lot about where we live; the latter, who we are.

Now there are many ways to illustrate what’s wrong with modern science. A good example is dissection. You will never find the meaning of a living creature by killing it. Pinning a frog to your lab table and slicing it into pieces, you may (if you are astute) discover the arrangement of its parts and how it jumps so high—but in doing so you will destroy an actual living creature and its jump. In effect, you purchase the scientific knowledge of its mechanism at the cost of whatever created significance it had in the world.

A second example I would offer is vaccines: not the concept of the vaccine, which is justified under bad enough circumstances, but what we might call the vaccine mentality—regarding the human being as a biological machine and medicine as a provider of designer additives to preempt every malady. This is a product of our blind faith in the ability of science to innovate every moment of suffering out of existence, which is delusional but intoxicating nonetheless. And that faith is symptomatic of the broader pharmaceutical way of life. My fourteen-year-old noted wryly the other day that one of the side effects mentioned in an ad for a new antidepressant was enhanced suicidal ideation: “It’ll make you happy, unless it makes you kill yourself.” (This ad was brought to us by Disney Plus, mind you.)

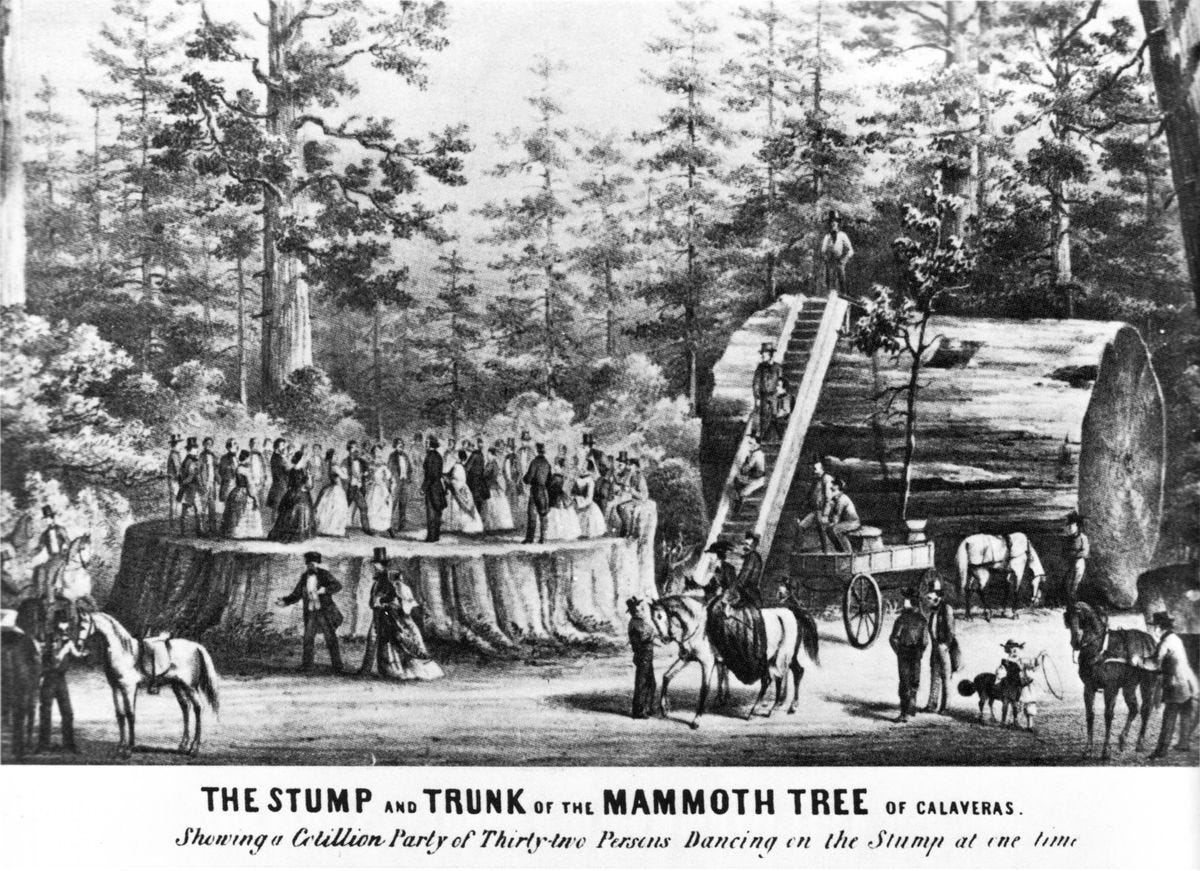

A third example concerns the efficiency with which we now reduce trees to lumber. Have you seen the videos of the harvesters that can fell, strip and buck an entire tree in something like 20 seconds? They are impressive machines, to be sure. Still, mixed with my fascination at these tree eaters is a nagging horror—not because I don’t love a nice hardwood table, but because there is something perverse about treating a forest like that.

Notice what happens when you see one of those videos: you are impressed not with the tree but with the machine. The tree itself becomes something defenseless and quite pathetic in the steel teeth of the harvester. It doesn’t even fall as a mighty or weighty thing, it’s taken by the claw of some higher power and doesn’t touch the ground until it is sawn into manageable pieces. Being thrown around like that, what had been a living giant rooted in earth, singing in the wind, is nothing but wood prepared for human usage. Something about that particular expression of efficiency dishonors the real value of trees, which is more than the board-foot price their wood will fetch on the market. It denies their inherent goodness. Seeing this contraption, Treebeard would lead the ents to war: “He has a mind of metal and wheels; and he does not care for living things, except as far as they serve him for the moment.” Treebeard said that of Saruman, but we all know Tolkien was, through Fangorn, talking about us.

Lewis adds, “We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams: the first man who did so may have felt the price keenly.” In other words, the reduction of creation to a catalog of mere material is the essence of disenchantment—it’s how you destroy meaning itself.

All of this originates with a modern science that can’t stop mechanizing everything it sees, can’t stop reducing, stripping, dissecting, depleting, “gnawing, biting, breaking, hacking, burning.” Science as it is today glares out of its cave, eyeing the creatures on the sunlit hills as nothing but fuel for the furtherance of human comfort, convenience, and power. It denatures everything it touches—strips each object in the world of its “qualitative properties,” that is, its significance, and reduces creation to a storehouse of lifeless things we might use. It is presently, in breathtaking fulfillment of Lewis’ prophecy, engaged in doing this with the human organism, the final frontier of man’s crusade to “conquer nature.” (You really do need to read The Abolition of Man. Go do it now. It’s his shortest book.)

All of this is the case because modern science is practiced by modern scientists—by men and women of whom the majority deny the Creator, and with him banish transcendent meaning altogether. As a result, our scientists don’t know how to work with or alongside the creational significance of any living thing—least of all a human being. They wouldn’t even know what you meant if you suggested things in the world have their own given meaning.

Lewis’ “regenerate science” would be different. It, too, would seek the human good—but not without honoring the good of the created world. Call me romantic, but I like to imagine that regenerate science would say the only man qualified to fell trees is one who loves their beauty and honors them in his heart as they fall; a man who only sees wood to be harvested would be sent back to school to read poetry about trees. Perhaps it would still find uses for vaccines—but it would never seek eternal life in injections. As Douglas Wilson writes in Angels in the Architecture, “We are not calling upon the works of modernity to die, but rather to grow up.”

There is cause for optimism. Consider the vastness of scientific learning at this point in history. We have answered the question “What is it made of and how does it work?” millions of times now. We know how cells operate, how all of the known chemicals interact, how to make metal objects fly, how to mass-produce microprocessors; we have special glasses that cure color-blindness, and implants that cure deafness. I live in San Diego, a sprawling county of 3.3 million people which can only exist because our drinking water is either desalinated out of the ocean or pumped out of Lake Havasu and piped 300 miles across the Mojave Desert.

The vision here is not to go backwards to a world without indoor plumbing or antibiotics. It’s to take all that we have learned about the physical world in the last three or four hundred years and enchant that knowledge with a sense of the transcendent meaning of all things.

Our idea (Lewis and me) is simply that scientists should practice their science in God’s created world, in submission to his laws, and in pursuit of his own way of viewing every last creature that he has made—seeing as they were all his ideas and sprang originally from his infinitely fertile imagination.

It’s safe to say our ability to manipulate the physical world for human flourishing has exceeded all expectations. But so far, what science has lacked is a workable vision of human flourishing. For that, you must read the Bible.

And this is my humble thesis: When scientists start reading the Bible and applying the gospel to their work, everything will change. If a majority of researchers and engineers acknowledged Christ as the King of their laboratory and repented of their hubris, we might finally have hope of a world in which our technology serves creation instead of exploiting it. What’s more, if you really listen to the whispers of possibility here, you will detect the real answer—the only right answer—to the urgent concern of the human impact on the environment. You say you care about climate change? Then worship Christ, because he is the only “world leader” who can do anything about it. And he is willing.

For my part, I have dissected precisely one animal in my life: a fetal pig in a biology lab at Portland Community College in the late 1990s. The only thing I learned was that I shouldn’t be studying biology. God designed my mind to latch onto scraps of meaning and integrate them into the story of the world he created and is now restoring. Integration is the opposite of dissection. And integrating thoughts and images is what it means to be a writer.

Others do well at the dissection table. They are where they should be, looking for cures to diseases—and good for them. I am glad for those people; I wish them well. But while they are busy cutting and probing, they should remember the sacrificial nature of their task: the fact that their subject has paid with its life for the production of their scientific insights. There ought to be an acknowledgement that one creature had to die so that others might live.

Deep in the heart of the scientific enterprise, then, the sacrificial vision awaits.

In this way, the gospel can even redeem the laboratory, and we might finally be on our way to unifying data and meaning, progress and preservation, technique and wisdom—a spiritually invigorated science which seeks the good of man within the restoration of the created world.